Chapter 1: Ohm’s Law and Electric Circuits#

Three Quantities#

Voltage. Current. Resistance. These three quantities will provide the foundation for our study of electricity, particularly electric circuits. Here I will outline their definitions and the equation which holds them together. In the next sections, we will develop an analogy to build our conceptual understanding, and apply this understanding to build an actual circuit. We need very briefly to dip our toes into the physics underlying electric circuits before we can arrive at the definitions. Chapter 6 will provide a more thorough treatment of this topic, but for now we will focus on the essentials.

The function of an electric circuit rests on a property of matter known as electric charge (often shortened to just “charge”). Physicists denote charge with a lowercase \(q\), and it is measured with a unit called the Coulomb (\(C\)). We can consider charge to be similar to mass, in that a particle has a certain “amount” of charge, just as an object has a certain “amount” of mass. The only difference is that while mass can only be positive (something can’t weigh \(-1\) kilograms), charge can be either positive or negative. In this respect electric charge behaves similarly to magnets: opposite charges (i.e., positive and negative) attract, while like charges repel.

Electrons, the subatomic particle of greatest relevance to us, have a charge of approximately \(-1.602\times10^{-19} \ C\). The reason we are most concerned with electrons is that in certain situations electrons, and hence electric charge, can move. This brings us to our first definition. Current, notated with the letter \(i\) (either uppercase or lowercase) is the rate of change of electric charge. In mathematical form,

Current is measured in Amperes (\(A\), sometimes shortened to “amps”), where one amp is equal to one Coulomb of electric charge moving past a given point in one second. Electrons are the usual “charge carriers” in a circuit; since they are negatively charged, the physical direction of current flow is away from an area of net negative charge towards an area of net positive charge. However, due to a quirk in the history of science, the direction of “conventional current” used in circuit analysis is the reverse, positive to negative. We will only consider conventional current from now on.

How can we make charge move? Moving electric charge from point A to point B requires energy (notated \(w\)), which leads to our second definition. The voltage between two points, notated with the letter \(v\) (either uppercase or lowercase), is the amount of energy required to move electric charge from point A to point B. In mathematical form,

Current is measured in Volts (\(V\), not to be confused with voltage itself), where one Volt is equal to one Joule of energy being used to move one Coulomb of electric charge.

An important idea to highlight in this definition is that voltage is relative, that is, we can only measure the voltage between two points. It is conventional to draw a plus sign at one point and a minus sign at the other point. These points are chosen such that the voltage of the “plus side point” relative to the “minus sign point” is positive, known as positive polarity.

What impacts the movement of electric charge and the amount of energy available to move it? This is our final quantity. Resistance, notated with an uppercase \(R\), is a material’s tendency to resist the movement of electric charge. Resistance is a property of materials, not particles, more analogous to density than mass. Various physical factors such as length and cross-sectional area impact the resistance of a material, but we won’t adddress those here. Resistance is measured in Ohms. (The symbol for Ohms is the uppercase Greek letter omega, \(\Omega\), since an English uppercase \(O\) looks too much like the digit zero. This is the first of many Greek letters we will use in our journey.) One Ohm is equal to a resistance of one Volt for every one amp of current. In fact, this describes the equation which is the title of this book, known as Ohm’s Law:

Making resistance the subject of the equation gives

So if we know how much current is flowing between two points, and the value of the voltage between them, we can compute the resistance present between those two points.

The Water Analogy#

Analysing electric circuits requires a good intuitive understanding of what is happening in the circuit. Greek letters and differential equations do not lend themselves to such intuition. The water analogy is a commonly used explanation for the three quantities introduced above. We begin by replacing electric charge with water. Electric current, being the flow rate of electric charge, becomes real current, being the flow rate of water. Voltage, the energy required to move electric charge between two points, becomes pressure, the energy required to move water between two points. The resistance of a material to the movement of electric charge can be imagined as a partially obstructed pipe, which limits the flow of water through it. These transformations are the basis of the analogy. But we will return to this description in the future and continue to flesh it out.

Power and Energy#

There is one more quantity which we need to know before we can start building our circuit. In general, physicists define power, notated with an uppercase \(P\), as the rate of change of energy. As an equation,

Power is measured in Watts (\(W\)), where one Watt is equal to one Joule of energy being used per second. However, we want to know specifically about electrical power. We can find this out if we multiply together our voltage and current quantities:

So electrical power is equal to the product of voltage and current. If a device is consuming energy, then its power value is positive. If it is supplying energy, then its power value is negative. This is known as the passive sign convention.

Building a Circuit#

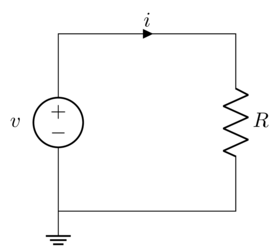

Okay. Let’s build our first electric circuit. To start, we need a path through which electric charge can move. A material which makes a good path is called a conductor. We will use copper wire, drawn as a straight line in our circuit diagram. Next, we need a source of energy to move the electric charge, known as an active element. This could be something like a battery or a generator or a solar panel. We will draw the generic symbol commonly used for an energy source in circuit diagrams. Finally, we need something to receive the power resulting from the voltage and current. This is called a load or a passive element. A load can be just about anything, from a light bulb to an entire house. The best way of modelling a load will depend on what the load is, but a simple load can be modelled as a resistance. We use a zigzag to show resistance on our circuit diagram.

There are two questions we must answer before we can finish our diagram. Firstly, in which direction is the flow of current? Since the source is supplying energy and the load is consuming energy, it is conventional to draw current flowing out of the source and into the load. This aligns with the passive sign convention, since the current flowing out of the source is in the opposite direction to the current flowing into the load.

Secondly, how do we measure voltage in our circuit? Remember that voltage must be measured between two points. In order to maintain consistency in our voltage measurements, it is helpful to choose a common reference point in our circuit, and always to measure voltages relative to that point. This common reference point is called the ground of the circuit. Whether or not it is literally the ground is irrelevant. We will choose the ground to be the bottom wire of our circuit, and represent this with a dashed triangle. Since we will measure all our voltages relative to the ground, we will give the ground a minus sign. The figure below shows our completed circuit diagram with the voltage, current, and resistances labelled.

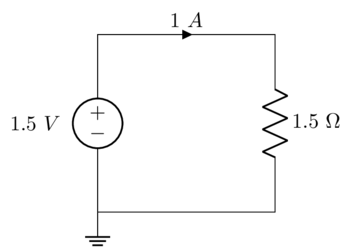

In Real Life: A Torch#

Electric circuits can often feel very abstract and unrelated to any physical objects. However, even our simple circuit above can provide a helpful description of an everyday item: a handheld torch. A torch is powered by a battery, which is a source. The lightbulb consumes power, so it is a load. A copper wire connects the two. We can even assign some typical values to our circuit quantities. A double-A battery is around 1.5 V. A medium sized torch might consume 1.5 W of power. Rearranging our power equation

We now know the voltage and current of our circuit, so we can compute the equivalent resistance of the lightbulb:

Our circuit diagram of lines and zigzags now takes on a greater meaning: it is an electrical model of a torch. In fact, most household devices which consume power can, at a basic level, be modelled with this same circuit.

Mathematics Corner: Ohm’s Law in Depth#

This inaugural Mathematics Corner contains a sneak preview of chapter 6. We will be using the more rigourous descriptions of voltage, current, and resistance for the vector form of Ohm’s Law.

We first define a vector \(\vec{J}\), called the current density. This describes the “amount” of current passing through a given cross-sectional area \(A\), such that

and the direction of \(\vec{J}\) is the direction of current flow.

One of the physical properties which effects the resistance of a material is its conductivity, notated with the Greek letter sigma, \(\sigma\). This is related to resistance according to

where \(l\) is the length of the material.

Finally, instead of voltage, we use the electric field vector \(\vec{E}.\) The vector form of Ohm’s Law is then given by

This is used more in physics and materials science than electrical engineering, but is good to be familiar with nonetheless.

What We’ve Learnt#

Electric current, \(i\), is the rate of change of electric charge, analogous to the flow rate of water.

Voltage, \(v\), is the energy required to move electric charge between two points, analogous to water pressure.

Resistance, \(R\), represents the ease by which electric current can flow through a material, analogous to obstructions in a pipe.

Ohm’s Law, \(v=iR\), describes the relationship between current, voltage, and resistance in an electric circuit.

Electric power \(P=vi\), where a source has negative power and a load has positive power.

Circuit diagrams are collections of symbols used to represent the key elements of an electric circuit.